When I say athlete, I’m not just referring to men and women getting paid to play a sport. I do work with pros occasionally but most my clients are what I call recreational athletes. They are the 45-year old mom of 3 who works her butt off in boot camp for an hour 5 days a week, the weekend half-marathon runners, the crossfitters, and the amateur body builders.

If you are training to decrease your fat mass, increase your lean mass or improve your performance through exercise and nutrition, YOU are an athlete. That means you should be eating like an athlete and ideally meeting with a nutritionist to help you set a functional plan and goals. Recreational athletes have a major disadvantage compared to pros because most pro athletes have access to nutrition and performance professionals on staff, coaching them on what to eat and what supplements (if any) would help them improve their physique or performance.

A big problem in the recreational athlete community is bro-science. Bro-science is a type reasoning popular in athlete circles (especially body building) where any ripped Joe Schmoe can hype a supplement or diet on instagram and is considered more credible than scientific research. The key here is: NOT backed by research. Just because a guy’s got a 6-pack doesn’t mean he knows what he’s talking about or that what he is doing will work for you.

Ergogenic aids

An ergogenic aid is any external influence that enhances athletic performance or facilitates physical exercise. This includes performance-enhancing drugs, mechanical aids, physiological aids, nutritional aids (supplements), and psychological aids.

If you decide to take a supplement or aid, it’s super important to know WHY you are taking it. “Because my trainer told me to” is not a good reason. I had personal trainer in my office recently who said: “I don’t take any supplements, only BCAAs sometimes when I’m feeling low on energy.” Unfortunately, that’s not what BCAAs do and that is NOT how they work. If you don’t know why you are taking a supplement, how to properly take it and when to take it, you are wasting your time and money.

To protein shake or not to protein shake?

Today we are talking about two of the most popular ergogenic aids, protein and BCAAs.

The general rule of thumb for calculating your protein needs is 1.2 to 1.4 g/kg of body weight for endurance athletes and 1.2 to 1.7 g/kg of body weight for strength and power athletes. For our 45 year old boot-camp mom who weighs 150 lbs (68.2 kg), that translates to a range of 82- 116 grams per day.

The greater the number of hours in training and the higher the intensity, the more protein that’s needed. Some research has recommended as much as 2 g/kg to prevent muscle loss in athletes who want to lose weight and have reduced their caloric intake.

Your body can only utilize so much protein at one time, so having a 20 ounce steak with a side of 8 egg whites and washing it down with a whey protein shake is overkill. Your body isn’t able to utilize it and is converting the excess protein to waste. Most studies support an intake of up to 2g/kg of body weight without any negative or adverse effects (including kidney damage). However, intakes above 2.5 g/kg of body weight puts you at risk of dehydration, fatigue, excessive caloric intake, and increased excretion of urinary calcium. Eating more than 200 to 400 grams of protein per day can exceed the liver’s ability to convert excess nitrogen to urea and lead to nausea, diarrhea, and other adverse side effects.

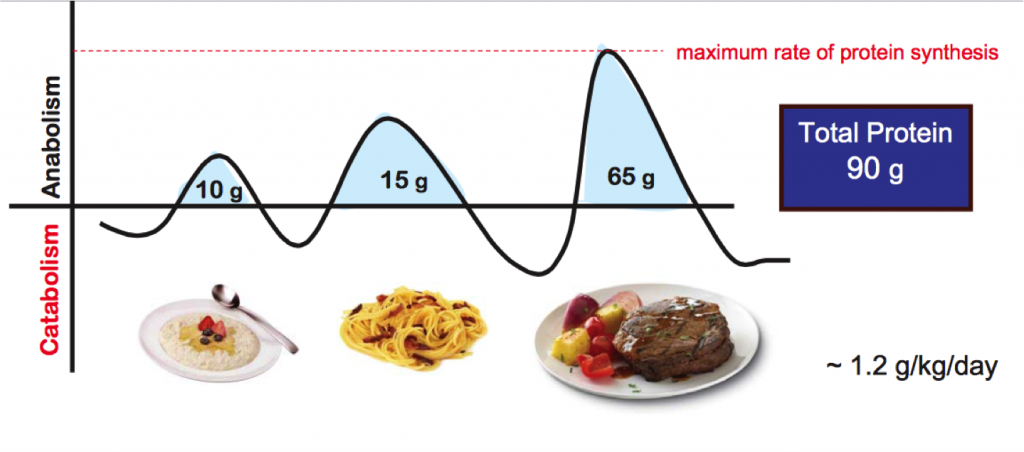

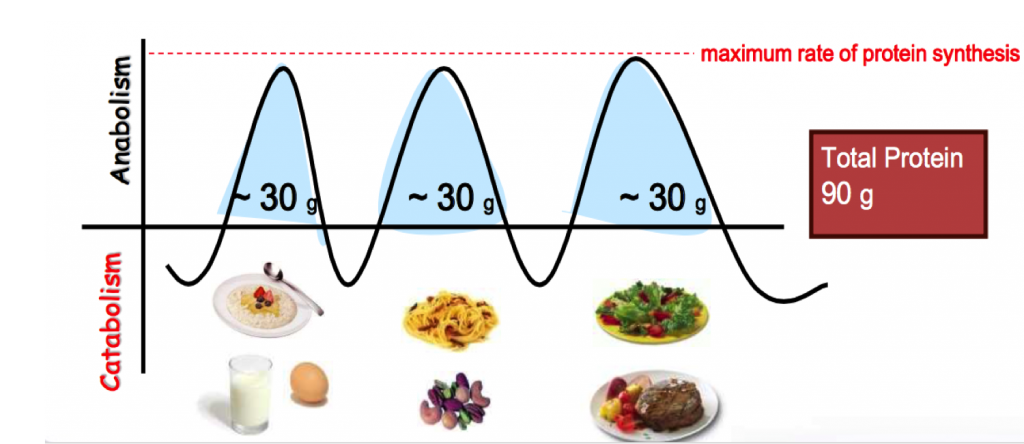

The maximal stimulation of muscle protein synthesis is achieved with a 20- 30 gram protein meal (depending on your size). Repeated maximal stimulation= increase/maintenance of muscle mass. Most people consume more than 65% of their daily protein in a single large dinner meal. That leaves less than 35% distributed among other meals and snacks. The total number of grams of protein per day is not nearly as important as how it is distributed throughout the day.

The two-hour post exercise window is the optimal time for muscles to uptake protein and enhance recovery. When you are in the gym doing resistance or strength training you are not building muscle. You are breaking it down and creating tiny little muscle tears. What you do immediately after exercise (nutritionally) is what will help repair and build those muscles back up. A 20-30 gram dose of protein 30 minutes post-exercise is ideal for muscle recovery. If you aren’t able to eat a meal after a workout for whatever reason, that’s when a protein shake or bar can fill the gap. If you have questions about what type of protein to use or bars to eat, read The Best Protein Powder and The Best Protein Bars. Do you NEED to use either of these things? No. You can get 20-30 grams of protein from real food and get the same results. Do they come in handy sometimes? Yes.

Important: Protein supplements on their own are NOT going to increase muscle. You have to do the work in the gym first to see any result.

Branched Chain Amino Acids (BCAAs)

BCAAs are essentially the building blocks of protein. Three amino acids (isoleucine, leucine, and valine) have been heavily researched for their potential to decrease muscle damage and soreness.

During prolonged exercise, plasma tryptophan (another amino acid) rises, causing feelings of fatigue. BCAAs compete with free tryptophan and can reduce your perception of fatigue. Less tryptophan goes to your brain, you get less fatigued, and experience higher performance.

However, if your fatigue is not due to an increase in tryptophan from prolonged exercise (e.g. you just didn’t get enough sleep last night), skip the BCAAs. They do not just miraculously increase your energy.

Leucine is also being researched for its role in preventing muscle loss and damage during resistance training. One study had subjects cycle for two hours at 70% of their VO2 max (the maximum volume of oxygen that an athlete can use) while supplementing with either a placebo or 12 grams of BCAAs per day. When supplementing with BCAAs, peak levels of enzymes reflective of muscle damage were delayed from two hours with placebo to five days for LDH (lactate dehydrogenase: an enzyme released from cells into the fluid portion of blood when cells are damaged or destroyed) and from four hours with placebo to five days with BCAAs for CK (creatinine kinase: another enzyme that can rise after muscle damage or heart attack). This led the researches to conclude that BCAA supplementation may help reduce muscle damage associated with endurance exercise.

Branched chain amino acids have also been found to decrease Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS) AKA second-day soreness caused by inflammation and fluid accumulation in the muscle fibers that occurs 12-48 hours after exercise. If you find that you lift legs on Thursday and still can’t run by Saturday, it’s time to try BCAAs.

The keywords here are slowing the breakdown of muscle and speeding up recovery. If you are in the gym lifting 2lb weights, you are probably not breaking down muscle and don’t need to speed recovery. If you do a gentle yoga class or a quick jog and 10 jumping jacks, you do not need BCAAs.

How much? The proven effective dose is between 5 and 20 grams. This can still be easily reached with protein-rich foods, because protein= BCAAs. That being said, the research on on BCAAs as ergogenic aids are on the three amino acids (isoleucine, leucine, and valine) as a stand-alone supplement (not as part of a food). There have been no detrimental side effects reported from BCAA use, however one study said that above 39 grams per day is detrimental.

When? Before exercise. If you are strength training, 5 to 8 g of essential amino acids (with 2-3 g of leucine) before exercise may help you minimize muscle damage and breakdown. Whey is 10% leucine, so if you drink a shake with 25 g of protein, you get 2.5 g of leucine.

For endurance athletes, 6 to 10 g of BCAAs per hour can delay fatigue.

How? Any food with protein is going to already have these amino acids, however I don’t often want to drink a protein shake right before a workout or have a steak. I would rather have BCAAs in capsule or powder form before and recover with food or a protein shake after.

Most powdered forms of BCCAs contain sucralose and other artificial ingredients because BCAAs on their own have an odd flavor. The brands with a ton of artificial sweeteners cover up the taste but tend to leave a slimy feeling on your tongue. I try to stay away from artificial sweeteners as much as possible, so my go-to brands for powdered BCAAs are:

If you want to skip the drink and take a quick capsule, I recommend Natura Formulas.

Look for a BCAA product that uses a 2:1:1 ratio of leucine: isoleucine: valine.

Stay tuned! I’ll also be covering caffeine, creatine, omega-3s, beetroot juice, carnitine and chromium picolate in later posts.

A note about supplement regulation: Unlike food, the FDA has no authority. There is no requirement of proven safety or effectiveness before entering the market. The FDA can not force recall and must prove beyond a doubt that a supplement is dangerous before removing it from market. What this means: I can vacuum up dirt and sell it as a moon rock dust metabolism enhancing powder. If I get some people to take some before and after photos and get Dr. Oz to pick it up on his show, I’m a millionaire.

As long as it’s not proven dangerous, no ones going to take it off the market. 70% of supplement companies inspected by the FDA from 2010 to 2012 failed to comply with basic GMP (good manufacturing practices) regulations. Six months after inspection, more than half of adulterated dietary supplements recalled between 2009 and 2012 were still on shelves. Look for products with a seal of certification like the ConsumerLab seal of approval or NSF certification. Unfortunately, no BCAAs without sucralose have these second-party certifications at this time.

If you need help losing weight, improving your performance or increasing your energy, contact me at megan@orlandodietitian.tin or schedule your appointment here. Not in Orlando but still need some nutrition tips? We also do online or over the phone consultations.

Resources

Reidy, P.T, D.K. Walker, J.M. Dickinson, et al. Protein blend ingestion following resistance exercise promotes human muscle protein synthesis. Journal of Nutrition 143: 410V416, 2013.

Dickinson, J.M., D.M. Gundermann, D.K. Walker, et al. Leucine enriched amino acid ingestion after resistance exercise prolongs myofibrillar protein synthesis and amino acid transporter expression in older men. Journal of Nutrition 144:1694V1702, 2014.

Layman, D.K., T.G. Anthony, B.B. Rasmussen, et al. Defining meal requirements for protein to optimize metabolic roles of amino acids. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 101(Suppl):1330SV1338S,2015.

Deutz NEP et al. Protein intake and exercise for optimal muscle function with aging: Recommendations for the ESPEN Expert Group. Clinical Nutrition (2014) In Press; http://www.clinicalnutritionjournal.com/article/S0261-5614(14)00111-3/abstract.

Kreider RB, Wilborn CE, Taylor L, et al. ISSN exercise & sport nutrition review: research & recommendations. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2010;7:1-43.

Dunford M, Coleman EJ. Ergogenic aids, dietary supplements, and exercise. In: Rosenbloom CA, Coleman EJ, eds. Sports Nutrition: A Practice Manual for Professionals. 5th ed. Chicago, IL: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2012:128.

Fink HH, Burgoon LA, Mikesky AE. Practical Applications in Sports Nutrition. 2nd ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2009:234-279.

Sizer FS, Whitney E. Nutrition Concepts and Controversies. 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Brooks Cole; 2011:400-406.

Webb, Densie PhD, RD. Athletes and Protein Intake. Today’s Dietitian. Vol. 16 No. 6 P. 22

Volek JS. Leucine triggers muscle growth. Nutrition Express. At http://bit.ly/1jNm3Dv