What are BCAAs?

Have you ever seen someone in the gym drinking neon colored liquid out of a shaker bottle during their workout? They’re probably drinking a BCAA supplement.

Branched chain amino acids, better known as BCAAs, are the building blocks of protein. There are nine amino acids that are essential, meaning that our bodies can’t make them and we have to ingest them from food. When you eat food that contains protein, you are automatically getting BCAAs.

There is no substantial evidence that consuming BCAAs in isolated supplement form is better than getting them from real food. Consuming protein (whether from a protein powder or food) increases muscle protein synthesis, which is why post-workout protein supplements are so popular. Three amino acids in particular (isoleucine, leucine, and valine) have been shown to induce the same increase in muscle protein synthesis as getting protein in its whole form.

Of the three, leucine has shown the most promise in its ability to decrease muscle soreness, stimulate muscle protein synthesis, and suppress protein breakdown. However, many of the favorable effects of BCAAs have been shown in rats and not humans.

Possible benefits

During prolonged exercise, plasma tryptophan (another amino acid) rises, causing feelings of fatigue. BCAAs compete with free tryptophan and can reduce your perception of fatigue. Less tryptophan goes to your brain, you get less fatigued, and experience higher performance.

However, if your fatigue is not due to an increase in tryptophan from prolonged exercise (if you just didn’t get enough sleep last night), skip the BCAAs. They will not miraculously increase energy.

One human small study showed that BCAA supplementation may reduce the muscle damage associated with endurance exercise.

Have you ever done heavy squats on a Monday and feel like you still can’t sit down without wincing on Wednesday? Branched chain amino acids may help with delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), which is caused by the inflammation and fluid accumulation in the muscle fibers that occurs 12-48 hours after exercise.

The keywords here are slowing the breakdown of muscle and speeding up recovery. If you’re doing Zumba, step, or another cardio-based class, you are probably not breaking down enough muscle to need to speed recovery. If you do a gentle yoga class or a quick jog, you do not need BCAAs. There is nothing wrong with those types of workouts, you just don’t need a supplement for them. If you are lifting heavy weights and having a hard time recovering, that’s where BCAAs may benefit you.

The downside

It seems like for every study that shows a benefit to BCAAs, there’s a counter study that argues it. A 2017 review stated that “the claim that consumption of dietary BCAAs stimulates muscle protein synthesis or produces an anabolic response in human subjects is unwarranted.” So whether BCAAs truly “work” as a nutritional supplement has yet to be proven in mass consensus.

When and how to take BCAAs

If you are strength training, 5 to 8 g of essential amino acids (with 2-3 g of leucine) before exercise may help you minimize muscle damage and breakdown. Whey is 10% leucine, so if you drink a shake with 25 g of protein, you also get 2.5 g of leucine. Any food with protein already has these amino acids. However, I don’t necessarily want to drink a protein shake right before a workout or have a steak. I would rather have BCAAs in capsule or powder form before and save the steak or protein shake for after.

For endurance athletes, 6 to 10 g of BCAAs per hour can help delay fatigue.

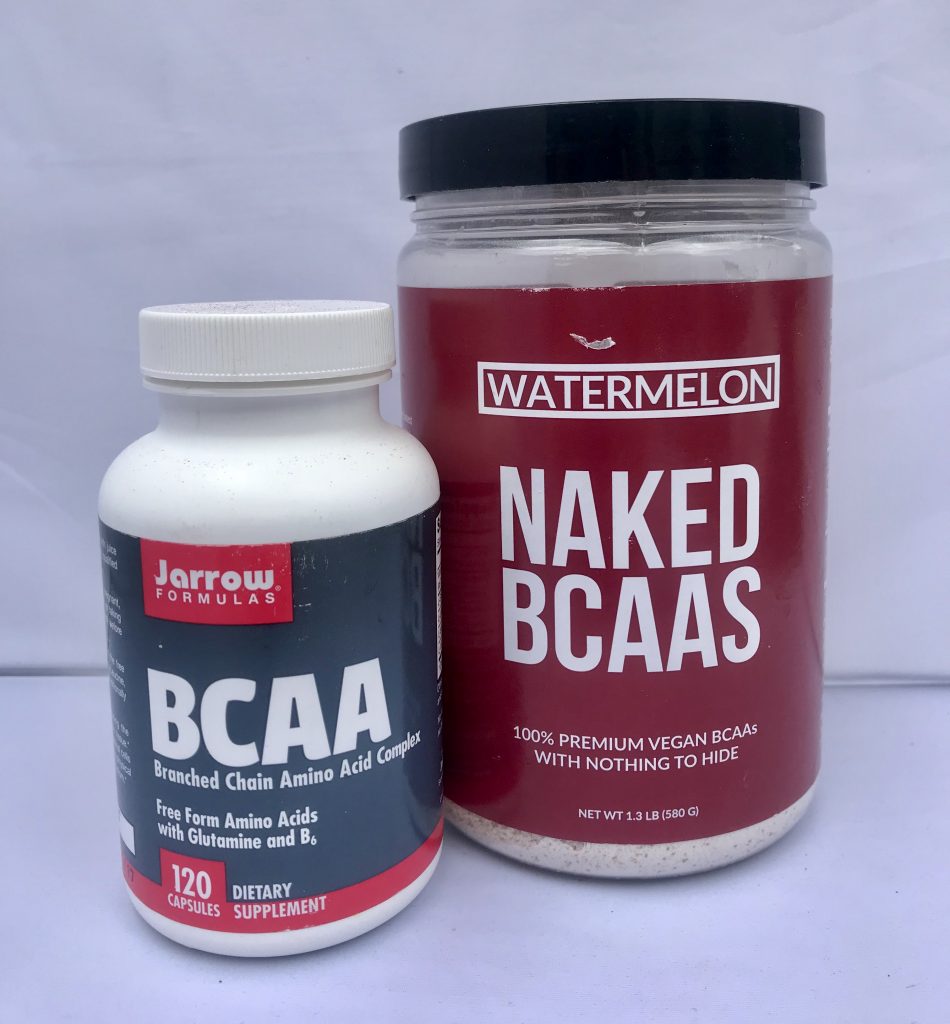

Most powdered forms of BCCAs on the market contain sucralose, artificial colors, and other sketchy ingredients. If you’ve read any of my other articles, you know I’m all about consuming foods and supplements in the purest form without any unnecessary junk. Look for a BCAA product that uses a 2:1:1 ratio of leucine: isoleucine: valine.

My go-to brands for powdered BCAAs are:

Capsules:

Read more:

References

Dunford M, Coleman EJ. Ergogenic aids, dietary supplements, and exercise. In: Rosenbloom CA, Coleman EJ, eds. Sports Nutrition: A Practice Manual for Professionals. 5th ed. Chicago, IL: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2012:128.

Fink HH, Burgoon LA, Mikesky AE. Practical Applications in Sports Nutrition. 2nd ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2009:234-279.

IOC consensus statement: dietary supplements and the high-performance athlete

Kreider RB, Wilborn CE, Taylor L, et al. ISSN exercise & sport nutrition review: research & recommendations. J Int SocSports Nutr. 2010;7:1-43.

Sports Dietitians Australia: BCAAs

Sizer FS, Whitney E. Nutrition Concepts and Controversies. 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Brooks Cole; 2011:400-406.